![Darren Sammy [Photo: AP]](https://www.thevoiceslu.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/sammy2.jpg)

Sydney, Australia – When Darren Sammy was a boy, West Indies cricketers were kings. Viv Richards, Curtly Ambrose, Courtney Walsh, Brian Lara – he loved them all. But none of them came from the lush Caribbean island of St Lucia, with its volcanic peaks and tropical breezes, where Sammy had been born in 1983.

“Cricket was the No. 1 sport but no St Lucian had ever made it,” Sammy says.

It was a wicketkeeper from another tiny island, Grenada, who inspired Sammy to play when he was in primary school. He watched Junior Murray play for the Windward Islands and then for the West Indies in their final glory years.

“When Junior Murray became the first Grenadian to play for the West Indies, we saw what the government did for him. He got a house, he got land, he got free gas for two years, a car to drive.”

Sammy’s hard-working parents, Wilson and Clara, had three children to feed by the time Clara was 23. Wilson made his living from a small banana plantation but gave it up to drive a minibus when the tourism industry took over the island.

Sammy resolved that when, not if, he made the West Indies team he would buy his father a new bus. “I kept my promise, and I have never been so proud to see the look on my dad’s face when he got it. Being able to provide for my family has always been at the forefront of my mind,” says Sammy, now a father of two boys and a girl.

“I grew up in a Christian home so one thing she [Clara] always instilled in me was to be humble and content with what she provided – but by no means does that mean you can’t reach for the sky. That is something I always understood.

“I always had the ability to be calm, I never let my peers or my surroundings affect who I am. I always knew what I wanted. I wanted to be a West Indies cricketer.”

There was a slight problem. The family’s Adventist faith meant Saturdays were for worship not cricket. And Clara wanted her eldest son to be a pastor in the church. But, before he was a teen, Sammy was dominating a secondary schools church cricket competition and spending most afternoons playing cricket with his friends among the mango trees in Micoud, his home district on the east coast of the island. Later, when national trials were on at the weekends, his grandparents gave him the money to travel to the St Lucian capital of Castries.

Eventually, it was a school principal who convinced Clara to let the budding all-rounder chase his cricket dream. Sammy went on to make his West Indies debut in 2004.

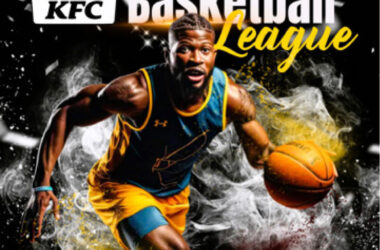

Sammy is a tall, strapping man with a winning smile. He can bowl long spells of medium pace and hit the ball a long way but he has never been the best player in the West Indies team. Sammy’s greatest attribute is his ability to bring people together.

That’s why, in 2010, he was asked to captain a West Indies team struggling to keep its best players from lucrative contracts in the Indian Premier League. Coach Ottis Gibson had earmarked the 2015 World Cup in Australia and New Zealand as a major goal.

The West Indies won the first two World Cups but have not lifted the trophy in Sammy’s lifetime. They haven’t been kings since 1995, when Mark Taylor’s Australians inflicted a famous Test series defeat in the Caribbean. Sammy remembers his father stopping work to follow that series. “The entire Caribbean was at a standstill, that’s how important cricket is.”

Sammy no longer leads the Test or one-day teams but feels a huge responsibility to restore some pride to the West Indies.

“We are several different islands with their own prime ministers, their own cultures. We come together as one to represent the Caribbean but it’s always difficult. But thanks to mum, I have this way with people. My character allows me to mingle and adjust to different cultures,” he says.

“I had only played nine Test matches when I was asked to captain, it wasn’t something I dreamed of doing, the selectors thought I could bring stability and leadership. I knew it would be tough, but I never back down from a challenge. I took it on knowing all the possibilities and it has made me stronger.

“The challenge for me was to be a consistent performer because the talk around was I didn’t command a position in the team. But I understood my role very clearly. I know I have never been an attacking bowler so my role was to be the workhorse, bowl long spells and if I get two or three wickets it’s good. That is the role I have been playing ever since I made my debut. I understood that, even if others did not.”

Sammy’s most cherished achievement, so far, has been to lead the West Indies to the Twenty20 world title in 2012. A beaming Sammy was pictured draped in the West Indies flag, dancing on the field with the rest of the team after the final in Colombo. It gave him a taste of what it would feel like to win the World Cup. “It means everything, not only to me but six million people in the Caribbean.”

The past 12 months has been a rollercoaster, for the West Indies and for Sammy.

In 2014, he was replaced as Test captain, and he retired from that form. Later in the year he was stunned to learn that Gibson had been sacked as coach on the eve of a home series against Bangladesh. Sammy was dropped from the team for a couple of games but recalled for the next series. Then, West Indies players shocked the cricket world and angered the powerful Indian cricket board by walking out on a one-day tour of India because of a pay dispute.

The players felt blindsided by their own union, the West Indies Players’ Association, says Sammy, which had agreed to a drastic pay cut without their knowledge. India launched a lawsuit that could have bankrupted West Indies cricket. World cricket bosses feared the West Indies’ participation in the World Cup was at risk.

Sammy insists this was never the case. “India is something I honestly wish had never happened,” he says. “I don’t think the game should ever suffer when you have disputes with player associations or board members. What happened in India was a situation where the fans and the public were robbed of an opportunity to witness their favourite team and their second-favourite team battle. That is something I don’t wish to be a part of and I don’t wish to ever happen again.”

Sammy had been part of a second-string West Indies team that was cobbled together when star players were on strike for the 2009 Champions Trophy. “It was not a good feeling. You don’t want to be seen as a replacement team,” he said.

“I have demonstrated that I am a devoted and committed cricketer for the West Indies. This time [in India] we just felt it was unfair, the terms and conditions they were asking us to play under [decided] without our knowledge. But not once did we think it would lead to West Indies not being part of a World Cup.”

Then, another bombshell. In December, captain Dwayne Bravo, fellow all-rounder Kieron Pollard and Sammy were axed from the one-day squad to tour South Africa, the basis of the World Cup squad.

Sammy was forced to confront the possibility that his World Cup dream was over. A couple of weeks later, he was reinstated, but Bravo and Pollard were cast into what their lawyer has described as “the political wilderness”, in apparent retribution for the India crisis.

Sammy says the omission of Pollard and Bravo is “unfortunate”, particularly as Bravo had only recently been named in the one-day international team of the year.

“It’s sad, you know, but we try to control the things we can. We don’t control the selectors, all we can do is try to perform to the best of our abilities. It could be my last World Cup so we want to give our best to our country.”

West Indies, under the fledgling leadership of 23-year-old Jason Holder have a chance to overcome the turmoil at the tournament in Australia and New Zealand. They are ranked eighth in world one-day cricket, but Sammy says that if they can click, they might be unstoppable.

He knows there is intense competition for his place in the team, that he needs to be at the top of his game, but is driven by the desire to do justice to the great, entertaining West Indies teams of the past. “We know our history and the world needs West Indies cricket at the top,” he says. “It’s up to us to keep the legacy going.”

First Published In The Sydney Morning Herald.

After I read these lines, I was moved beyond explanation “I know I have never been an attacking bowler so my role was to be the workhorse, bowl long spells and if I get two or three wickets it’s good. That is the role I have been playing ever since I made my debut. I understood that, even if others did not.”

The WORKHORSE. If this doesn’t inspire you, I don’t know what will. Work your tail off. Hard work can dwarf talent any day.